The unnerving similarities — and key differences — between our current moment and the Cold War, explained by an expert.

When Russia invaded Ukraine last February, Vladimir Putin said the world was facing a confrontation between the civilizations of the West and Moscow. This division into two camps evoked memories of the Cold War, and, as in those days, Russian leaders again openly discussed using nuclear weapons.

There’s a major difference between today and half a century ago — Moscow looks far weaker than the former empire of Stalin and Brezhnev. Putin’s forces have failed to achieve nearly all their goals in Ukraine, and many of the USSR’s satellite states are now NATO members. Ukraine was once part of the Soviet Union, but its ties to the United States and the European Union have never been stronger.

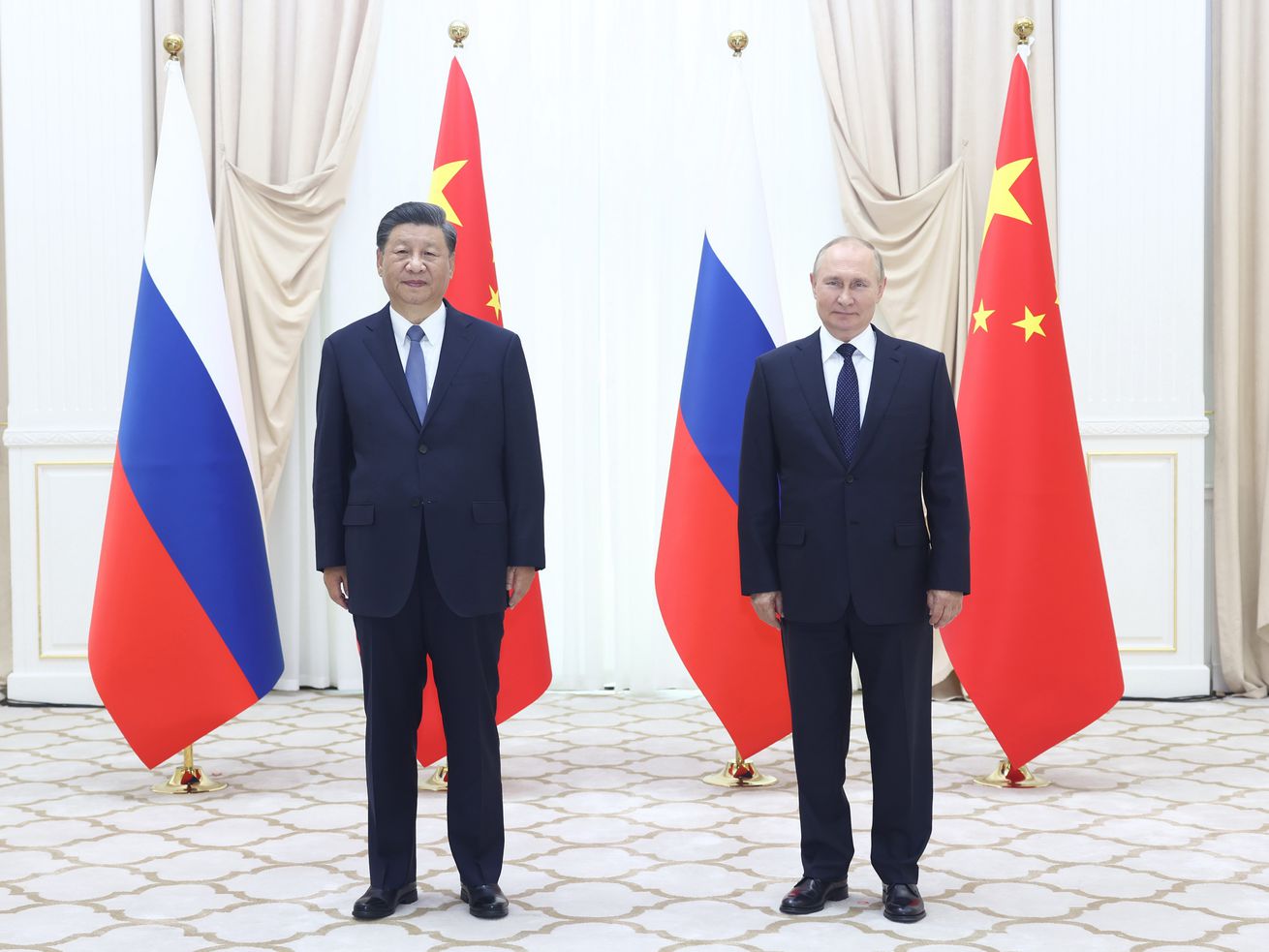

Yet many recent trends also resemble the contours of the Cold War. Moscow and Beijing have become staunch allies — closer than even during the communist era. Chinese President Xi Jinping is pursuing his openly declared ambitions to oppose the global power of the United States. Since the invasion, meanwhile, the US and EU have made a series of moves to completely sever trade relations with Russia and to halt the development of China’s tech sector.

Is the world splitting again into two hostile blocs, just as during the Cold War? To find out, I spoke with Sergey Radchenko, a historian of the Cold War and the Wilson E. Schmidt Distinguished Professor at the Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies.

A transcript of our conversation follows, edited for length and clarity.

Michael Bluhm

Observers have long said that the world is dividing into democratic and authoritarian countries. President Joe Biden has approached global politics with this frame, and many of his actions have only heightened the division; he organized a democracy summit, and he’s talked about creating a league of democracies. Xi Jinping, meanwhile, has cast China as an alternative model, more efficient than the Western one. The hostility between the bloc of mostly democratic, mostly Western countries and the Beijing-Moscow camp seems at least superficially similar to the Cold War era of two rival blocs.

How much does the global political dynamic today resemble the Cold War?

Sergey Radchenko

There are some similarities but also vast differences. The distinguishing feature of the Cold War was the two sides’ different conceptions of modernity and how to get there. There were different approaches to the notion of property and to the economy — central planning in the Soviet Union and China or a market-oriented economy in the West. The ideological distinction today is authoritarianism versus democracy. This is a very big difference.

But at the level of everyday life, there are a lot of similarities among Russia, China, and the West: restaurants run by private individuals, the service sector, and people everywhere have iPhones — if they can get them now in Russia.

Another interesting distinction is that the connections between Moscow and the West were not as strong during the Cold War as they are today. Even though the West has tried to expel Russia from the world economy, it is still intricately connected. Natural resources still flow out of Russia, and Russia depends on imported goods. Moscow still trades with the world — it is not an autarkic system.

Those connections are even stronger with China. If you compare China today to China during the Cold War, it’s night and day. Superficially, there are similarities between these two periods, but if you dig deeper, you see great differences.

Michael Bluhm

You mention that the Cold War was also a conflict of political and economic ideologies. How would you compare the ideological dimension of global politics today to the Cold War?

Sergey Radchenko

If you look at Russian and Chinese ideology today, you’d have to ask, What exactly is it?

If there is a Russian ideology, it’s ethnic nationalism. China’s case is also largely nationalism. In China, nationalism began to displace communism as an ideology in the 1970s, after the Cultural Revolution. It comes from the disappointment of the population with ideological dogma and with the great promise of a communist revolution that never happened. The Chinese Communist Party was facing a legitimacy deficit, and they were looking for things to fill it — so nationalism replaced communist revolution. The same thing happened with the Soviet Union falling apart; the Russian Federation had to reinvent itself on the basis of Russian nationalism.

Nationalist ideology exists in many other places. Nationalism is not at all a new ideology, but it’s not the same as during the Cold War.

Michael Bluhm

But can nationalism function as a unifying ideology for a bloc of allied countries? Iran’s theocracy, for example, also has a prominent nationalist element. But do these parochial nationalisms create limits for any alliance?

Sergey Radchenko

They do. And even when China and the Soviet Union had a common ideology in the 1960s, they were the worst of enemies. In 1969 they fought a border war, and the Soviets threatened to use nuclear weapons. A shared ideology is by no means a guarantee that you will not have a really nasty relationship.

Just before Russia invaded Ukraine, Putin went to Beijing, and the countries issued a joint declaration that had an ideological underpinning for the first time in recent memory. It talked about opposing an American conception of world order. I’m not sure where this ideological dimension is going.

You mentioned Iran earlier. Iran is becoming closer to Russia and supplying weapons to Russia for the war against Ukraine. Russia, China, and Iran have joint military exercises. I would call it an alignment and not an alliance. What is the basis for this alignment? They share an anti-American agenda. But beyond that, their interests don’t converge all that much.

Michael Bluhm

Let’s stick with China for a moment. China today is very different from the China of the Cold War. It’s far more powerful militarily, economically, and politically. As Xi Jinping has consolidated power in China, relations between Beijing and the West have worsened. Even EU leaders such as Margrethe Vestager speak openly now of an adversarial relationship.

Is China today playing the role that the Soviet Union did in the Cold War?

Sergey Radchenko

China is the leader of this new alignment, but I don’t know that China has the ambition to be the new Soviet Union. The Soviet Union had the ambition to transform the world. Is China interested in preserving the international order and just improving its place in it? Or are they trying to replace the international order? Do the Chinese have a grand strategy?

We don’t have a clear view of what the Chinese are thinking, nor do I think the Chinese know what they want. They have proposed a series of stratagems such as the Belt and Road Initiative. They talk about “win-win” and a “Chinese dream.” These things are vague, and it’s not clear what they entail — and whether they entail undoing the existing structures of the international order.

From the Chinese perspective, the world is looking more chaotic, and the Chinese are trying to take advantage of this chaos. But it’s not clear that they have the same sort of single-minded pursuit of global transformation like the Soviet Union did through Marxist-Leninist ideology.

Michael Bluhm

For many, the Cold War comparisons were revived when Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. But Russia seems to have made a terrible mistake. It appears much weaker than a year ago — and weaker than the Soviet Union. Where does Russia stand today?

Sergey Radchenko

Putin obviously miscalculated. He was looking forward to a more chaotic world where he felt Western influence was declining, and he perhaps thought that he could improve Russia’s relative position by invading Ukraine. It was a very poorly thought-through idea.

This is where the Cold War connects to today: Russia has always felt that it does not get enough respect in global politics. That feeling is rooted in the Soviet past. This was a key preoccupation of Soviet leaders from Stalin to Khrushchev, Brezhnev, Gorbachev, and even to Yeltsin after the fall of communism. They felt that the Soviet Union or Russia should exercise a prominent, central role in global politics, and that the United States was not willing to give it that place in the system. That’s a major continuity.

Michael Bluhm

After the invasion of Ukraine, the West experienced newfound unity and moral clarity, with overwhelming condemnation of Putin and support for Kyiv. But then inflation rose to highs not seen in decades, and steeply rising energy costs have caused protests in many European countries. How does Western unity look today?

Sergey Radchenko

The jury is still out. Western unity has been much greater than one might have supposed back in February 2022, but Putin is playing the long game. He thinks he can outlast the West. He thinks this unity will not last once something goes wrong — an economic downturn or recession, the rise of populism in Europe, or a new president in the United States. This ability to wait and to plan for the long term underpins Russian policy at the moment.

Putin also thinks that he can create disagreements among European countries. This is a Cold War parallel; it’s a time-tested Soviet and Russian approach to international politics, in particular to Europe. During the Cold War, the Soviets’ key priorities were to push the United States out of Europe and undermine European integration.

But Russia, just as the Soviet Union did, has consistently underestimated its ability to bring Europeans and Americans together. If Russia or the Soviet Union did not do stupid stuff like invade neighboring countries, there would be a lot less unity among European countries. Stalin threatened Berlin in 1948-49, so NATO was created in 1949 as a response. Stalin threatened Turkey, so Turkey joined NATO. In 1979 and throughout the 1980s, there was the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. The Russians try to play on the contradictions with the West, but they also pursue stupid policies that bring the West together against them.

Michael Bluhm

But many powerful countries in Asia and the Middle East do not fall into either of these blocs. India, for example, has skirmished with China along their shared border, but Delhi has maintained robust trade ties with Russia. Saudi Arabia warmly welcomed Xi recently, in a visit that irritated many in Washington who saw Saudi Arabia as a longstanding US ally.

How do you see other countries approaching the new global dynamic?

Sergey Radchenko

I don’t think they like this at all. They like a much more multipolar world, where they can maintain their freedom of action. India never liked the idea of a divided world. That is why they pursued the policy of non-alignment since Jawaharlal Nehru became prime minister in the 1940s. It’s a time-tested tradition.

Today, the relationship among China, Russia, and India has the kind of flexibility lacking during the Cold War. During the Sino-Soviet alliance in the Cold War, if India and China had a conflict and the Soviets tried to stay neutral, the Chinese said, You’re betraying your obligations as an ally. Today, when the Chinese and the Indians have a conflict in the Himalayas, the Russians can just say, We’re sorry, but that’s your business. And China and India will accept that. The Global South would much prefer not to have a world divided strictly into a system of two blocs and alliances.

Michael Bluhm

So is the world today more like the bipolar Cold War, when it was split into two camps, or is it multipolar — meaning many competing centers of power?

Sergey Radchenko

A lot of people say that today’s world is different from the Cold War precisely in that respect. There’s something to it, although this bipolarity was falling apart since the 1970s. China disconnected from the Soviet Union and then exited the Cold War — and was even aligned with the United States against the Soviet Union.

Today, there is a tendency toward the solidification of two blocs, as we saw with Biden’s effort to create a bloc of democracies. But I don’t think it’s going to fly, because of the economic underpinnings of the world system, the redistribution of wealth to new countries, and the emergence of new centers of power. Those are real things.

Michael Bluhm

What does a more multipolar world mean?

Sergey Radchenko

It’s a very interesting question, because the world may become much more chaotic as new centers of power try to redefine the world in a way that suits their interests. That is what Putin was trying to do by invading Ukraine. He was thinking he could capitalize on this by acting in a rough and unexpected manner. He miscalculated with regard to Ukraine, but I don’t think he miscalculated in his interpretation of where the world is going.

We are moving more in the direction of diffuse centers of power, with many states unwilling to be drawn into either of these new blocs. I’m not even sure that China and Russia will emerge as a bloc. They will maintain their distance and their own internal contradictions, though they will probably not allow those contradictions to spill into a conflict as during the Cold War.

What Sundance movies reveal about the angry “good guy.”

Cat Person — the movie adaptation of the New Yorker short story that took over your Twitter feed in December 2017 — starts with a now-familiar paraphrase of a Margaret Atwood quotation: “Men are afraid that women will laugh at them,” says the on-screen text. “Women are afraid that men will kill them.”

The crowd laughed nervously when the words appeared at Cat Person’s Sundance premiere. It’s a solid précis for the film, which chronicles the doomed relationship of 20-year-old Margot (Emilia Jones) and a very tall guy named Robert (Nicholas Braun). They meet at the movie theater where she works behind the concession counter. They have a bracing and thrilling text message relationship, followed by a far less scintillating in-person one, and then it all goes south.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24381081/catperson2.jpg) Sundance Institute

Sundance Institute

The movie is good, till it isn’t; director Susanna Fogel deftly pushes Margot’s interior narrative into a visual medium by adding secondary characters (like best friend Tamara, played by the always fantastic Geraldine Viswanathan), cleverly deploying dream sequences, and rendering Margot’s squirmy experience with visceral precision. But there’s a third act tacked on that destroys the ambiguity of the original story. In the short story, we’re left with lots of questions, the way you would at the end of such a relationship. But the film tries to tie the loose ends up, and the result is maddening.

Still, I mostly enjoyed it. And the Atwood paraphrase kept churning in the back of my mind, because I started ticking off the other films I’d just seen at Sundance that could have claimed it as well. There’s a particular type of “good guy” who breaks into an incandescent rage when his ego is bruised — when he suspects, in other words, that women are laughing at him — and rendering him recognizably on screen in a risk-averse, male-driven Hollywood hasn’t always seemed possible. This Sundance proves it is.

In Cat Person, for instance, Margot finds herself desperate not to assert her own aversion to having sex with Robert, and tells herself it’s just easier to go through with it. He’s bigger than her, and she’s worried throughout about putting herself in danger. But in his bedroom, she’s no longer afraid that Robert, who’s still mostly a stranger, is some kind of deranged serial killer luring her into a trap. She just worries how he might react if he feels slighted — and does something she really regrets because of it.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24381078/fairplay.jpg) Sundance Institute

Sundance Institute

Margot’s sentiment feels well-paired with Fair Play, another of the festival’s buzziest films, a relationship drama inspired by, if not actually hewing to, the outlines of an old-school erotic thriller. (Netflix picked up the movie for a cool $20 million, so you’ll be able to see it soon.) This time the couple at its center, Emily and Luke (Phoebe Dynevor and Alden Ehrenreich), are rising high-finance stars who have to hide their relationship at work. But when she’s promoted over him, things turn sour.

Fair Play is caustic and enthralling, but mostly it’s the kind of movie that makes you wince with recognition — or, in any case, if you’ve ever made yourself small to avoid the rage of an insecure man. Luke seems like the best sort of supportive boyfriend until he senses that others are laughing at him, that the life he’s desperately convinced he deserves to lead is on the verge of toppling, and that Emily, who adores him, might look at him through a different lens.

What comes into sharp relief in Fair Play — and in Cat Person, for that matter — is that for these men, the kind who pride themselves on being “good guys,” the women they’re dating aren’t the problem. These women are accommodating and supportive far beyond their own comfort. It’s that these men believe that they deserve something (a woman, a job, a very particular type of respect) simply for existing; when they get even a whiff of the opposite, they snap into verbal and physical violence.

Maybe you’ve never run into this; maybe you’ve never experienced it firsthand. But I assure you someone you love has. I know I have. What both movies manage to do, and what’s hard to do in any other medium, is put the viewer in the mental space of the women who find themselves cowering or even just worrying that their very reasonable confidence and sense of self-worth will threaten a man, and that there will be consequences.

Crucially, both films are less about the individual characters than the world around them. It’s a world that cultivates men like Luke and Robert, makes them promises it can’t fulfill, and then gives them tacit license to strike out when they don’t get what they want. That’s why they feel of a piece with Justice, a documentary by Doug Liman about the allegations against now-Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh, and what the women who accused him endured as they took their story into the public eye.

Justice centers mostly on Deborah Ramirez, who alleges she was the subject of grotesque harassment by Kavanaugh while a student at Yale. Ramirez’s story has been told, but for the film she revisited the story and talks about the aftermath of making the accusations. Cut together with the congressional testimony of Christine Blasey Ford and Kavanaugh’s own hearings prior to his confirmation, it’s a pretty brutal film to watch.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24381080/kavanaugh.jpg) Sundance Institute

Sundance Institute

But what sticks out in concert with movies like Cat Person and Fair Play is the vehemence — which reads, on screen, as almost inexplicably explosive — with which Kavanaugh denied the allegations. His anger. His inability to exhibit the cool-headed humility you’d expect from someone on the nation’s highest court. The small lies he told for no reason, which the movie establishes with journalistic rigor. His blistering, red-faced rage.

It’s like you’re watching Luke or Robert explode at Emily or Margot, in a manner all out of proportion with whatever they’re exploding about, because there’s a lot more going on here than anger about perceived mistreatment. It’s the fury of someone who’s been crossed, the foolish spiraling panic of a child who’s had their toy snatched away. And on screen, you can watch it, and see how ugly and irrational it is. You can’t walk out of one of these films feeling comforted and comfortable. They are testimony to the broken world we’re living in, and how very, very far we have to go.

Fair Play, Cat Person, and Justice premiered at the Sundance Film Festival. Cat Person will be distributed by Netflix; Fair Play and Justice are currently awaiting distribution.

What’s lost when focusing on the cute and charismatic. Plus: Why Teslas keep catching on fire, the progressive case for more people, and others.

This edition of The Highlight is a collaboration from across the Vox newsroom, a wide-ranging exploration of the policies and personal practices that could make the world a better place.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24368824/glennharvey_2023_01_07_vox_popgrowth_final.jpeg) Glenn Harvey for Vox

Glenn Harvey for Vox

Yes, you can have kids and fight climate change at the same time

The progressive case for population growth.

By Bryan Walsh

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24368868/lede_animation_revised.gif) Praveeni Chamathka for Vox

Praveeni Chamathka for Vox

We pulled pandas back from the brink of extinction. Meanwhile, the rest of nature collapsed. (coming Wednesday)

The trouble with the conservation’s cutest mascot.

By Benji Jones

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24368876/vox_1.jpeg) Gianna Meola for Vox

Gianna Meola for Vox

You may be thinking about animals all wrong (even if you’re an animal lover) (coming Wednesday)

Philosopher Martha Nussbaum says humans should grant equal rights to animals, even in the wild. Is she right?

By Sigal Samuel

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24368888/STORY_5_SET_6.jpeg) Shaneé Benjamin for Vox

Shaneé Benjamin for Vox

The glories of dining out alone (coming Thursday)

Solo dining is one of life’s great pleasures — and privileges.

By Alissa Wilkinson

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24368897/glennharvey_2023_01_07_vox_tesla_final.jpeg) Glenn Harvey for Vox

Glenn Harvey for Vox

Why Teslas keep catching on fire (coming Friday)

EVs catch fire far less often than gas-powered cars, but firefighters still need to adapt.

By Rebecca Heilweil

CREDITS

Editors: Adam Clark Estes, Libby Nelson, Alanna Okun, Lavanya Ramanathan, Brian Resnick, Elbert Ventura, Bryan Walsh

Copy editors: Kim Eggleston, Elizabeth Crane, Caitlin PenzeyMoog, Tanya Pai

Art direction: Dion Lee

Audience: Gabriela Fernandez, Shira Tarlo, Agnes Mazur

Production/project editors: Susannah Locke, Nathan Hall